Peacekeepers find they're now a military force, with an enemy

By David Abel | The Star-Ledger | 4/11/1999

PETROVIC, Macedonia -- The radio in Sgt. 1st Class James Lashelle's Humvee crackled.

"X-ray, this is Blue 5, we're taking direct fire," the voice said — calmly, almost casually. "We're in contact. They're all over us."

The message came during a routine patrol for Lashelle of Clinton, Iowa, and his company. The American soldiers had been patrolling the rocky border between Serbia and Macedonia for several weeks.

When the words of Staff Sgt. Christopher Stone, a 25-year-old father from Smiths Creek, Mich., came across the radio, the platoon sergeant thought his gunner was joking. "I didn't hear the edginess in his voice," Lashelle, who was cruising through the brush about three miles away, said last week. "But I should have known. Sergeant Stone would not have made a joke like that."

In 30 seconds, the radio had gone dead. Stone and two other cavalry scouts, Staff Sgt. Andrew Ramirez, 24, of Los Angeles, and Spc. Steven Gonzales, 24, of Huntsville, Texas, were gone. The trio from the 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry of 1st Infantry Division had been snatched by the Serbs.

"I was very frustrated," Lashelle said in an interview Wednesday. He and other Americans here talked about losing three comrades and what it is like to be a part of an action that started as a peacekeeping mission and is now is military one.

Lashelle and the missing men came to Macedonia from their home base in Schweinfurt, Germany. Like U.S. soldiers before them, they thought they were going to be U.N. peacekeepers. Instead, they became part of a NATO force.

The U.S. presence is not welcomed by ethnic Serbs who live along the border in Macedonia. While the ethnic Albanians who have been expelled from Kosovo appreciate their help, many in Macedonia don't.

Sgt. Ronald Hintay, 29, of San Diego, feels the pressure. This is his second tour in Macedonia. In 1995, he remembers locals smiled and waved as his convoy passed. Then, their Humvees were painted white and their helmets were blue, signifying their relationship with the United Nations. Even when NATO launched a month-long bombing campaign against the Bosnian-Serb forces later that year, the border remained quiet, Hintay said.

Conditions along the border, especially in ethnic Serbian areas within Macedonia, began to change when the United Nations mission ended in February. The bitterness has only increased since NATO began its bombing campaign March 24.

Now, at least 12,000 NATO troops have replaced the U.N. soldiers, which include about 500 U.S. soldiers, up from 350 when it was a U.N. operation. The blues and whites have been painted green. And there is more firepower.

"It's really become a hostile environment," Hintay said. "Soldiers used to marry locals and go downtown all the time. Now, you can't go there . . . It makes me disappointed. We're trying to help this country."

Some of the newly arrived U.S. soldiers are just confused.

Spc. Rachel Dawson, 20, of Cleveland, arrived in Camp Long here in Macedonia little more than a week ago from the 504th Brigade's base in Fort Hood, Texas. Taking a water break, Dawson, one of the few American women serving here, confessed she had little idea what the war was about.

"Really, I don't know why we're bombing Serbia," she said. "I just know what I hear on CNN. Someone's trying to get some land. I don't know."

Other soldiers said they understood the tension. They know they may be among the vanguard likely to push into Kosovo, whether as peacekeepers or as an invading force.

"The Serbians are killing the ethnic Albanians, and we're here to stop it because they're committing crimes against humanity," said Spc. Damon Harris, 26, of Springfield, Mo. When asked if he worried about an invasion, he answered, "Mine is not to ask who or why, but to do or die."

For now, American soldiers in Macedonia are patrolling the border. But there is evidence everywhere that their role has changed. When they were part of a U.N. peacekeeping mission, they flew flags and advertised their presence. Then they were observers.

Not now. Now they're a military force with an enemy.

Beefed-up patrols move surreptitiously along the border. Soldiers carry more ammunition and are required always to carry weapons and protective vests. They're also authorized to use deadly force if attacked.

"Everyone is very concerned about retribution," said Lt. Col. Jim Shufelt, commander of the U.S. forces here. "It's possible we can be shelled or there can be a terrorist attack. Anything is possible."

Like more soldiers being captured by the Serbs. Shufelt is adamant that Stone's patrol didn't cross the border as the Serbs say. He believes the patrol was ambushed in Macedonia.

By David Abel | Houston Chronicle | 4/10/1999

By David Abel | Houston Chronicle | 4/10/1999

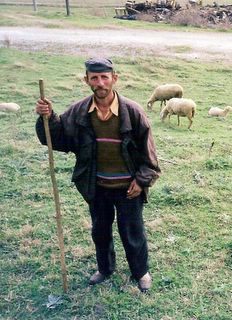

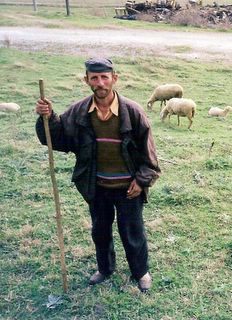

BRAZDA, Macedonia - To the sheep farmer, the scores of red government buses rounding the narrow road seemed like part of the normal flow of traffic between Yugoslavia and Macedonia.

Little did Fahdil Seruhe know that the buses rumbling through his valley were packed with thousands of weary ethnic Albanian refugees from Kosovo.

And little did Seruhe, an ethnic Albanian himself, realize that the land where his sheep have grazed for the past 20 years was surrounded by Europe's most chaotic refugee crisis since World War II.

"What crisis? I haven't heard about a refugee crisis,"  said Seruhe after he chased a stray sheep from the busy road. "I don't like politics. I try not to get involved."

said Seruhe after he chased a stray sheep from the busy road. "I don't like politics. I try not to get involved."

The refugee crisis took some local villagers by surprise. Yet in the 17 days since NATO began raining bombs on Yugoslavia, two massive camps have sprung up near this illiterate 42-year-old farmer's grazing grounds.

NATO officials say that what had been a chaotic response to the refugee influx in the war's first two weeks now is being shaped into a coordinated effort.

"The humanitarian effort continues to gain momentum, and I think it will be a matter of days before we have the situation quite under control," Sadako Ogata, the head of the U.N. refugee agency, told an Associated Press reporter.

South of Seruhe's land, where the buses were headed, stands a new tent city that was built to accommodate up to 100,000 refugees. In less than two days, NATO troops mainly from Britain, France and Italy erected the sprawling camp with the help of at least 50 U.S. Marines.

The NATO camp sports rows of sturdy new tents rushed from the United States, Italy and Britain. Multiple food stations are supplying about 30,000 refugees with bread, chicken, military rations and potable water. There are medical facilities. More importantly, refugees say, there is a sense of security.

"When the Serbs forced us to leave Pristina and said they would kill us if we didn't, it was bad," said Lindita Latife, 21, who studied math at a university in Kosovo's provincial capital.

"Then we got to the border, and the Macedonians treated us like animals," Latife said. "First, they wouldn't let us enter. Then they made us sleep on the open, wet ground. And then they beat us when we complained. It's only now that we have some peace. This is a great place - even if I still can't take a shower."

To the north of Seruhe's fields - in a border settlement called Blace - stand the remnants of a ramshackle camp where Latife and thousands of other ethnic Albanians stayed until they were removed by Macedonian police earlier this week.

The empty area is a portrait of squalor. Human waste, bottles and hastily discarded possessions and clothing litter the muddy paths.

The makeshift tents in the camp had offered little protection from the cold rain. Food had become scarce, and diseases such as respiratory viruses and skin rashes had flared.

At least 40 people are reported to have died at Blace, according to the U.N. refugee agency.

The Macedonian government, which has been overwhelmed by the flood of refugees, controlled the Blace border camp. Troops surrounded the cramped grounds brandishing AK-47s. Human rights workers and other monitors were barred from entering the fields. And customs officials were responsible for the slow admission and release of the exiled Kosovar Albanians.

Many frustrated ethnic Albanians - who had been forced to wait up to four days in the open and in the range of Serbian guns in hopes of crossing the Macedonian border - have now returned to the interior of Kosovo, their fates unknown.

Some refugees are being settled in camps in Macedonia such as the NATO tent city at Brazda, which Ogata toured Friday. Others are being sent to facilities in NATO member countries or in Albania.

The United States and other countries have pledged to take thousands of refugees, but U.N. refugee officials indicated Friday that any plans to send the Kosovars to North America are on hold for now because of desires to keep them closer to their homes.

Critics have charged that the dispersal of refugees would only help Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic complete his apparent goal of ridding Kosovo of ethnic Albanians.

The residents at Brazda seem grateful. "The NATO troops have been wonderful," said Ramadan Ibrahimi, a 27-year-old taxi driver. "I saw them playing ball with children."

Despite the gravity of the refugee crisis, some Macedonian villagers such as Seruhe live as though nothing has changed.

The sheep farmer, who says he rarely ventures more than a few miles from his home, had no idea that bombs were falling on neighboring Yugoslavia or that thousands of his fellow ethnic Albanians had been driven from their homes.

He said he was merely enjoying the arrival of spring.

"I have a job to do," he said, "and that's what I do. I don't pay attention to conflicts.

"They don't make sense to me."

On Symbolic Day, Refugees Gain Asylum

By David Abel | Defense Week | 4/26/1999

PETROVIC, Macedonia - Only a few hours before nightfall Monday, when Israel would begin observing Yom Hashoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, a gleaming Boeing 737 lifted off the tarmac of Macedonia's principal airport, heading to Tel Aviv with 111 refugees from Europe's worst ethnic conflict since World War II.

None of the men, women or children recently exiled from Kosovo had ever visited Israel, a nation founded in 1948 in the wake of wartime genocide and ethnic persecution of Jews. Some of the ethnic Albanians said they knew little about the country they were being taken to, other than it had set up an efficient field hospital in their refugee camp. Others, however, knew exactly why they were going to Israel.

"We have had a very similar fate as the Jews," said Astrit Kuchi, a 24-year-old medical student forced from his home at gunpoint in Kosovo's capital Pristina. "I think they understand us better than anyone. If they can't help us, no one can."

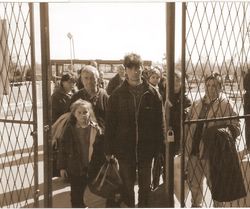

The refugees spent much of the previous three weeks on the cusp of hell. Serbian police forced them from their homes, sent many marching miles through snow-capped mountains and pushed them into a disease-infested no man's land. Later, some were separated from their families as Macedonian police hastily herded them into sprawling refugee camps.

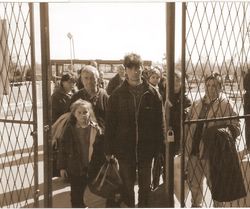

The ethnic Albanians came to Petrovic International Airport in four city buses. Most wore the same clothes and hadn't showered since leaving their homes in the embattled southern province of Serbia. Pregnant women, babies sucking pacifiers, unshaven old men, unkempt teenage girls and young men lugging their family's few possessions slowly emerged from the buses as their names were called.

Names such as Hasani, Ramadini, Hamid. Distinctively Muslim names. Going to a land that uneasily grapples with the ethnic tensions of its own Muslim citizens.

Lost fathers

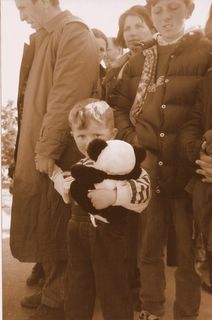

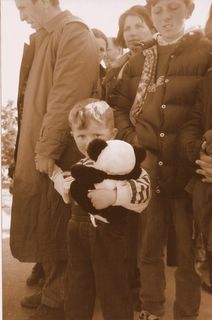

"I am going to Israel," beamed Kujtim Cerimi, 4, clutching a panda bear he calls Monkey. "We will find a home there."

The little boy walked through a metal  detector holding his uncle's hand. No one knew where his father was. He might have been dead or just in another refugee camp. Or somewhere searching for food near the family's burned home in the Kosovar village of Fushe. But Kujtim and eight others from his family collected their blue boarding passes and shuffled toward the Israeli passenger jet to start a new life.

detector holding his uncle's hand. No one knew where his father was. He might have been dead or just in another refugee camp. Or somewhere searching for food near the family's burned home in the Kosovar village of Fushe. But Kujtim and eight others from his family collected their blue boarding passes and shuffled toward the Israeli passenger jet to start a new life.

Onboard Flight 100, the refugees found red and yellow nylon tote bags in their seats. Inside were a few welcoming gifts: a white baseball cap, a bag of chocolates, an Israeli flag with its Star of David. Watching the refugees' tattered luggage roll into the cargo bay, the flight's captain, David Vernick, observed, "That's usually about enough bags for one family."

Next to Vernick stood a row of Israeli dignitaries who had flown in a few hours before to deliver eight tons of medical supplies. Included in the entourage was Irana Raslan, the 22-year-old Palestinian recently crowned Mrs. Israel.

"Israel doesn't care if they are Muslim, Christian or Jewish," she said, watching as muddy shoes scurried up a staircase and 105 adults and six babies boarded the flag-draped airplane. "We came to help because these are people who are suffering."

Ran Curial, Israel's ambassador to Greece, said he expected his country would likely accept more Kosovars over the next few weeks. Israel is well-adapted to taking in refugees and large immigrant populations, he said. It accepts on average 50,000 new residents every year and previously has admitted refugees from wars in Bosnia, Rwanda and Ethiopia.

Next stop: Kibbutz

While many of the refugees may eventually return to Kosovo, Curial said they would be housed on a Kibbutz near the city of Haifa, where they would be given language training and opportunities to find work in their fields.

"It is very symbolic that this is happening on Yom Hashoah," Curial said during a tour of Israel's field hospital at the refugee camp in Brazda, which had tended to more than 700 patients and delivered six babies in its first six days of operation. "My feeling, and the feeling of many Israelis, is that we have to do what people did not do 55 years ago."

Shehide Ramadani wasn't sure where she was going last Monday, but she was sure it would be better than where she came from. The 19-year-old English student from Pristina watched as Serbs in black masks pillaged her home. Her father later was separated from her family in Macedonia. She believes he's in Germany.

Ramadini and the five family members heading with her to Israel learned about the openings because their tent in Brazda was near the Israeli hospital. It was the first ticket out of misery, she said.

"Really, I'm not sure where I'm going or what I will do," she said. "But these people helped us when we needed help in the refugee camp. I believe they will help us more."

Copyright, Defense Week

As exiles seek a life, Macedonia sees its delicate balance shift

As exiles seek a life, Macedonia sees its delicate balance shift

By David Abel | The Star-Ledger | 4/14/1999

SKOPJE, Macedonia - Pushing his way through the frenzied crowd, Servej Bela scuffled to secure a place in front of a small window at the local Red Cross last week.

Unlike thousands of ethnic Albanians fenced in in camps, this 19-year-old was not seeking bread, shelter or medicine.

He, like hundreds of others, was pleading for Macedonian identity cards.

Thirty-three cousins from Kosovo, who have taken refuge with Bela's family in a cramped two-room house, need the cards so they can resume their lives. They want to go to school, get medical aid and qualify for food supplements from international relief agencies.

The university student, who found his Kosovar cousins less than two weeks ago in a squalid refugee camp on the Macedonia-Serbian border, left empty handed. Authorities in this small, bucolic country of 2 million people, one of Europe's poorest, are concerned that the influx of ethnic Albanians will severely upset their nation's delicate ethnic and political balance.

Local Red Cross officials would not say how many identity cards will be issued. However, government officials have clearly encouraged refugees to stay in camps and have resisted settling the exiled in Macedonia.

More than half of the estimated 125,000 Kosovars sent here since NATO began its bombing campaign on March 24 have been taken in by friends, family or other ethnic Albanian host families, according to the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees.

Before the war, ethnic Albanians accounted for at least 23 percent of Macedonia's population. That doesn't include an estimated 50,000 to 100,000 Kosovars who took refuge here last March as tensions mounted in their home province inside Serbia. And many fear, as the war continues, more will flood across the border.

Life for ethnic Albanians in this recently established country has improved since Macedonia gained independence from Yugoslavia in 1992. While as Muslims they have long been second-class citizens - the country is 70 percent Orthodox Christian - they find less isolation and more opportunities.

The nascent democracy,  the only Yugoslav republic to peacefully separate from the former Communist country, has increasingly incorporated ethnic Albanians into influential positions throughout the country. They hold several powerful ministerial positions, including the job of vice premier. In the most recent national election in October, for example, the winning party, which had more than 60 percent of the vote, welcomed an ethnic Albanian party into its coalition.

the only Yugoslav republic to peacefully separate from the former Communist country, has increasingly incorporated ethnic Albanians into influential positions throughout the country. They hold several powerful ministerial positions, including the job of vice premier. In the most recent national election in October, for example, the winning party, which had more than 60 percent of the vote, welcomed an ethnic Albanian party into its coalition.

Still, discrimination continues. "The bottom line is there are long-standing tensions between the ethnic Albanians and Macedonians," said a U.S. diplomat at the embassy in Skopje. "The situation has gotten much better in recent years. But they aren't out of the woods by any means."

Macedonians worry that their country might turn into another Kosovo, Serbia's embattled southern province, with ethnic Albanians demanding independence or a "Greater Albania."

''That's what they want," says Vancho Petrov, 33, a Macedonian taxi driver, echoing comments heard from many locals. "I know these people. They will want to take a piece of our country for themselves."

But inside Bela's dilapidated two-room home, his Kosovar cousins laugh at the idea of a greater Albania. They say they just hope to live in their country again. Thirteen of them are younger than 16 years old and have none of the exuberance of a gaggle of kids in such close quarters.

Bela says his cousins are in good hands at his home. But he isn't sure how long his family can bear the burden. For the last two weeks, all they have eaten is tea and bread.

''We need help," Bela says. "Who knows if they will ever be able to return to Kosovo. They need to have lives to live of their own."

The voice of Bela's 12-year-old cousin, Gadaf Shiti, is high pitched as he speaks of revenge and promises to join the Kosovo Liberation Army. His mother, who walked three days without food or water to reach the Macedonian border, says she approves of her son's desire to fight. Gadaf's aunt can't get up from a small bed. Her legs won't hold her weight. Too much walking, she says.

They don't know what they'll do if the war doesn't end soon. For now, they'll stay with Bela's family and try to live as best they can as ethnic Albanians in Macedonia, they say.

''Someday I will go back," vows Sheride Shiti, 30, Gadaf's mother. "But it will never be the same. There are too many tears."

David Abel | Houston Chronicle | 4/14/1999

SKOPJE, Macedonia -- When Kosovo refugees began pouring over the Macedonian border a few weeks ago, authorities here in one of Europe's poorest countries issued a plea for help.

NATO answered the call. Soldiers erected massive tent cities, manned food stations, set up field hospitals and kept order in the camps.

Now, NATO is gradually removing itself from the humanitarian mission, handing control of the camps to Macedonian authorities and international relief agencies.

But the fading of NATO's presence has left many refugees worried.

"When we got here on the border, they treated us like animals," Lindita Latife, 21, said of Macedonian police at the refugee camp where she first stayed.

"I don't want to be at their mercy again."

Last week, Latife, an ethnic Albanian from Kosovo's capital of Pristina, was moved to a sprawling tent city built by NATO troops.

Scores of Kosovars interviewed in refugee camps said they were harassed by Macedonian authorities. All spoke of their desire for NATO troops to remain their guardians.

"The horror only got worse here," Lebibe Ibrahimi, 34, an elementary school teacher from Pristina, said of her arrival in Macedonia. "The police separated my family. I still don't know where they are. They beat us."

NATO officials say that much of the control over the camps will be in the hands of relief organizations, such as the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees. Yet Macedonia will have sole responsibility for the refugees' security.

"The handover will be a process, not an event," promised Simon MacDowall, a NATO spokesman in Skopje.

Paula Ghedini, a spokeswoman for the U.N. refugee agency, said the United Nations has offered sensitivity-training classes to Macedonian police.

"In other operations, we recognized that police in most countries are not used to dealing with vulnerable populations," she said. "They're used to dealing with criminals."

Kosovar Albanians say they have another reason for being anxious about the Macedonian takeover of the camps. Ethnic Albanians, who make up about 23 percent of Macedonia's population of 2 million people, have long borne the brunt of discrimination, they say.

As Muslims speaking a different language than the Orthodox Christians who dominate the country, ethnic Albanians are treated like second-class citizens, the refugees say. Many Kosovar Albanians believe that most Macedonians sympathize with the Serbs.

"If you cut the Macedonian with an ax, seven Serbs come out," said one refugee at a camp in the village of Stankovic who asked not to be named.

On a recent night, thousands of men, women and children ambled about the garbage-strewn refugee camp in the village of Brazda, trying to keep warm. Some made small fires. Others walked along the camp's fence for exercise or to stave off boredom.

When refugees came too close to the barbed wire fence, beefy Macedonian police officers patrolling the perimeter with machine guns barked out orders to keep clear.

Arbana Rrustermi, 19, who left Kosovo with only a bag of clothes, said she hopes that the police stay outside the camp's fences.

"They were making jokes as women and children were dying," she said. "They were just cold. I saw them beat people. I saw them beat an old woman. They kicked her when she was on the ground.

"I will never forget that."

A hunted editor dodges death to bring the news to refugees

A hunted editor dodges death to bring the news to refugees

By David Abel | The San Francisco Chronicle | 4/15/1999

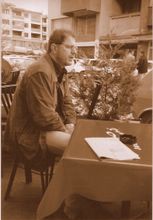

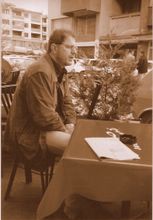

TETOVO, Macedonia -- Two weeks ago, sitting alone in the basement of a friend's vacated home, Baton Haxhiu watched on CNN as colleagues, foreign reporters and NATO officials pronounced him dead by summary execution.

Haxhiu, editor-in-chief of Kosovo's leading ethnic Albanian newspaper, Koha Ditore (Daily Times), froze. He thought about his wife and 3-year-old boy. There was nothing he could do. He was a hunted man.

''It was very hard for me," said Haxhiu, 33, who recently surfaced in this largely ethnic Albanian city in northwest Macedonia. "But I was on the Serbs' list. I knew what they would have done if they found me."

On the morning of March 23, the day before NATO began raining bombs on Serbia, Haxhiu (pronounced Hah-GEE-you) drove to his office in the Kosovo capital of Pristina and found blood on the newspaper's front steps. A security guard had been killed, the daily's press burned, all the computers in the office smashed. Before "fining" him 300 German marks, Haxhiu says, police at the scene told him the newspaper would never be published again.

But the bearded editor is moving to prove the Serbs wrong. Next week, with contributions including $150,000 from the British government, Haxhiu and his scattered team of reporters intend to deliver their 24-page broadsheet for free to the thousands of refugees living in camps in Macedonia and Albania. They also plan a new Web site - Serbs destroyed Koha Ditore's previous server, according to Haxhiu - and to take testimony from refugees to document alleged war crimes for the International Criminal Tribunal in The Hague.

''What our people need right now is a sense of community," said Haxhiu, sipping a beer at a swanky cafe in Tetovo between hugs from friends and cell phone calls. "They do not have enough information. They don't know who is alive or dead or where their families are. We want to help."

Indeed, a quick tour through any of the sprawling tent cities dotting Macedonia provides a sense of how desperate the refugees are for information. Some ask foreigners to borrow cell phones and quiz them on the war. Others ask for batteries to supply their radios.

Few appreciate the value of news as much as Haxhiu. For 10 days, he moved surreptitiously from basement to basement, from mosques to friends' homes, hoping to avoid the Serbian onslaught sweeping Kosovo. His only possession was a radio.

He wanted to know what had happened to other intellectuals reported killed by Serbs after attending the funeral of a Kosovar human rights lawyer. He learned later that many of them were also alive. "The only important thing for me was the news," he said.

Haxhiu has worked as a journalist since writing for his university's newspaper in Pristina. In March 1996, with tensions mounting as Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic cracked down on Kosovo's nearly 2 million ethnic Albanians, he started the independent Koha Ditore. The paper criticized not only Milosevic's repression, but also the growing movement toward armed resistance supported by the Kosovo Liberation Army. For its stance, the newspaper's employees became victims in the emerging conflict. Serbian police frequently harassed distributors and sometimes beat them. Haxhiu was repeatedly interrogated.

After 10 days dodging marauding paramilitary units, Haxhiu found his opportunity to escape. Through the basement window of the neighborhood mosque where he had been hiding, he saw thousands of legs scurrying in the streets. He previously had shaved his auburn beard to disguise himself. He put on a hat. When he got outside, he saw a young woman holding a baby. " 'From now on, I am your husband and this is my child,'" Haxhiu told the woman, who immediately recognized him. "She just said, 'You're alive!'"

The soft-spoken journalist sped away with the woman and child in his red Volkswagen Golf. His own wife, son and parents remained in Pristina.

Four days later, with the help of the leader of Macedonia's ethnic Albanian political party, he crossed from Kosovo into Macedonia untouched by Serbian police. He emerged in London, where Britain and other Western nations pledged to help him launch Koha Ditore in exile.

Working out of a friend’s small, unadorned office and spending most of his time exchanging news with friends from Kosovo at the café, Haxhiu says the only obstacle in his path may be the Macedonian government.

This small former republic of Yugoslavia has long discriminated against its ethnic Albanians, which account for at least 23 percent of its population. Many Macedonians fear their recently established country could turn into another Kosovo, with ethnic Albanians seeking independence o a greater Albania.

Haxhiu says he’s concerned that "paranoid" government officials might ban him from publishing in Macedonia. But he’s confident that the paper will be in the hands of refugees by next week.

"Our plan is to publish," he says. "The refugees need news. We will provide it."

Nearly $1 billion in weapons shipped

By David Abel | The Boston Globe | 7/4/1999

WASHINGTON - Following a pattern of supplying future foes with high-tech weapons, the United States furnished Yugoslavia with nearly $1 billion in arms during the past five decades, according to the Pentagon's Security Cooperation Agency.

After Slobodan Milosevic came to power in 1987, the United States continued the flow of weapons, including fighter aircraft, tanks, and artillery. In all, $96 million in arms and training was provided for the Milosevic government before 1991, when war in the Balkans brought the program to a halt.

The United States, which dominates the world's arms trade, sold or gave away more than $21 billion in weapons to 168 nations in 1997, the last year statistics were available, according to Demilitarization for Democracy, a group in Washington that advocates arms control.

"President Clinton justifies today's record arms exports to dictators as a way to gain influence and encourage reform," said Caleb Rossiter, director of

Demilitarization for Democracy, saying that at least 52 recipients of US arms are nondemocratic nations. "But the billion-dollar military investment in Yugoslavia's dictators was justified in the same way. Kosovar civilians suffered from this policy and US forces were placed at risk."

US officials have long claimed the lucrative arms sales have a purpose beyond profit.

During the Cold War, the prime justification was that by providing arms to countries such as Somalia or Iraq, both of which later used US weapons against American soldiers, the United States ensured their clients would be under US influence instead of that of the Soviet Union. Furthermore, officials argued that recipients of arms from America were more likely to promote US interests and contribute to regional stability.

But since the fall of the Soviet Union, a significantly new justification for continued arms sales has emerged: maintaining the US military's industrial base in a decade of declining defense budgets.

"This is not a black-or-white issue," said Wade Boese, a senior research analyst at the Arms Control Association, a Washington think tank. "Money is definitely a factor, and arms sales provide the United States with influence on the way militaries develop. But the key point is that weapons outlast the regimes they're intended to support."

Examples abound of US arms sales to friendly governments turned unfriendly. In Iran, the United States had helped prop up an autocratic ally during the 1960s and 1970s with the latest F-14 fighters, Hawk missile batteries and modern destroyers. But when the shah's corrupt regime was toppled by Muslim fundamentalists led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the new regime usurped the modern weapons, instantly becoming a powerful enemy of the United States.

Similar examples can be found in many countries, including Panama, Haiti, Liberia and Afghanistan. And in some cases, weapons supplied to countries still close to the United States have been used for purposes the US government later condemned. In Turkey, arms provided by the United States have been used to repress the country's Kurdish minority.

The United States first began supplying Yugoslavia with arms in 1950, after the nation's leader, Josip Broz Tito, refused to join the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact. US military exports to Yugoslavia that decade included 15 F-84G Lockheed Thunderstreak fighters, 60 M-47 tanks and hundreds of artillery pieces and antiaircraft guns, valued then at more than $723 million.

Military sales fell off in the next two decades but picked up again after Tito's death in 1980. In the 1960s and 1970s, the United States sold Yugoslavia a mine countermeasure ship and millions of dollars worth of sophisticated electronic equipment. In the 1980s, the US government and US companies sold the Balkan nation $193 million in air-to-surface missiles and air defense radar systems, some of which may have been fired at NATO planes during the 11-week air campaign that ended in June.

"It doesn't help to just slap on an embargo after you provide all these arms," said Anna Rich, a researcher at Washington's Federation of American Scientists' Arms Sales Monitoring Project.

The best way to make sure this kind of thing doesn't happen again is by Congress passing a general code of conduct."

A bill was introduced on the floor of the House last month that would prohibit arms sales to nondemocratic governments that fail to protect human rights, engage in armed aggression and do not fully participate in the UN Register of Conventional Arms.

As the bill has so far been drafted, there would be two exceptions: The president could request Congress to exempt a country if it is in the national security interest to provide military support to that nation or if there is an emergency and a vital interest of the United States is threatened.

Many longtime weapons specialists, such as retired Admiral Eugene Carroll, said a code of conduct is long overdue. He said US weapons have been turned against US diers too many times, he said. He also indicated US arms may have been used in war crimes such as those committed by Serbian forces in Bosnia and Kosovo.

"The solution is to quit leading the world in the arms trade," said Carroll, now deputy director of the Center for Defense Information, a Washington think tank. "The fewer arms in the world, the better for the United States. There is just less potential for violence."

By David Abel | Defense Week | 4/26/1999

NORTH OF KUMANOVO, Macedonia -- Scores of ethnic Albanian children lined the narrow dirt road, raising their fingers in the victory sign as the convoy of French troop carriers ground through their villages to its base hidden in the mountains.

The soldiers packed into the large vehicles wore Kevlar helmets, armor-plated flak jackets and gripped 7 pound Famas assault rifles. Some aimed their weapons from hatches in the roof. Others tossed chocolate bars to their well-wishers.

"NATO, NATO!" the children yelled in support as the stocky Renault-built vehicles passed through one village recently with pink tulips sprouting near a row of red tile-roofed homes.

"It makes me feel good to see them," said Pfc. David Bicuse, 19, on his first trip out of France. "They are happy to see us. We're a force of good. We're here to protect the peace."

The French haven't always been eager to be identified with NATO. But an afternoon on patrol with soldiers from France's 8th Parachute Marine Infantry Division shows how Paris is coming back into the fold. In 1966, President Charles de Gaulle forced NATO to move its headquarters from Paris to Brussels and removed France from the alliance's military command to protest U.S. domination.

The decision, taken in the midst of the Cold War, was the culmination of years of Franco-American rivalry over control of the alliance. Despite the tension, France retained its membership in NATO's political wing and has maintained close military ties to the alliance. Over the years, French forces have taken part in allied exercises, have had a role in NATO air surveillance and have shared military infrastructure such as fuel pipelines and communications. In 1991, France demonstrated its solidarity with NATO countries when President Francois Mitterrand committed French troops to the Gulf War.

Rapprochement didn't begin until shortly after NATO bombed Bosnian Serbs in late summer of 1995-the alliance's first sustained combat operation in its history. A few months later, with 60,000 NATO troops poised to launch the alliance's first peacekeeping mission, President Jacques Chirac decided France would resume attending NATO military meetings. Paris, however, stopped short of rejoining the alliance's integrated military structure.

French leaders say they won't fully join the military wing until Washington agrees to surrender control of NATO's southern military command to a European officer. They believe Europeans should have more power. Allied Forces Southern Europe, which includes the U.S. Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean, has always had an American officer in charge. And the United States has said it won't let its sailors serve under foreign command.

'We are NATO'

Like many of the nearly 2,500 French soldiers serving here in NATO's Allied Rapid Reaction Corps, those in France's 8th Parachute Marine Infantry Division consider themselves as much a part of the alliance as soldiers from the United States and Britain. They fly a bright orange swatch of plastic on top of their vehicles to identify themselves as members of NATO, exchange food rations with other alliance members to keep a variety (though, of course, the French say their meals are superior) and at night they hear the same bombs exploding on the other side of the border.

"We are not isolated," said Capt. Eme Paravisini Bruno, who commands the paratroopers and admits nervousness increased among his ranks after Serbs captured three U.S. soldiers. "France is in it with NATO. Our mission is united. We are NATO."

When the convoy of armored personnel carriers rolled into Matejche, a small village on the Macedonian-Kosovo border where one-fourth of the population is ethnic Serbian, the French soldiers heard the same insults reported by Americans and British troops. As the patrol stopped to buy fresh meat on a road separating 100 Serbs and their Orthodox church from 300 ethnic Albanians living beside a mosque, locals emerged from homes and stores to either cheer or jeer the paratroopers.

"It's not just Clinton who is fascist," said Aleksandar Dehevic, 23, an ethnic Serbian farmer certain the Serbs would prevail against the alliance. "Any of the countries in NATO are no better than Hitler. They're terrorists."

A few miles further north into the foothills of the Sar Planina mountains, which separate Macedonia from Kosovo, the convoy arrived at a checkpoint with soldiers donning red berets and machine guns. The guards cleared the personnel carriers to climb a muddy trail that wound through a thicket and opened into the paratroopers' modest camp. On a broad, open slope, scores of soldiers spent the afternoon munching souffles and rationed crackers, cleaning their weapons and smoking cigarette after cigarette.

"We are waiting," said 1st Sgt. Raufauore Etera, 24, watching a pot of tea boil. "Our job is to stay out of danger until we are needed."

The final answer

Like the other 12,000 NATO soldiers spread throughout Macedonia, the paratroopers' mission grows less clear by the day. French troops were dispatched here with a force of only 12 helicopters, 12 light tanks and 29 armored personnel carriers to await a peace agreement. However, as NATO's bombing campaign stretches into its second month and Serbian leaders remain intransigent, it's increasingly unlikely NATO will shift roles from making war to enforcing peace.

"We will do what we are told," said Lt. Baure Christophe, 28. "If our orders change, we will respond."

New orders could include taking part in a ground assault on Serbian forces holding Kosovo, Serbia's embattled southern province. That prospect may have gained currency last week when Chirac said in a televised speech that the alliance should apply "additional means" besides escalating the air war to stop "massacres, rapes, burned villages, families separated and thrown onto the roads."

French officials reportedly said Chirac's statement was an allusion to ground forces, and that France's plan was to seek a U.N. Security Council resolution mandating such a force, though such a request would almost certainly face a Russian veto. Gearing up to return to France's principal base 15 miles from the border in Kumanovo, a loud thud echoed from across the border. High above, against a bright blue sky, two streaks of white condensation streamed from the wings of a NATO fighter.

Capt. Bruno tightened the strap on his camouflaged helmet and secured his flack jacket. After climbing into one of the returning armored personnel carriers and rising through a hatch holding his Famas, he squinted into the distance and pondered the war.

"We hear the reports of atrocities as everyone," Paravisini said. "We want them to stop. Maybe we are the only answer."

NATO Bombs Serbs With Leaflets

By David Abel | The Boston Globe | 05/09/1999

WASHINGTON -- On one leaflet, the caption beneath a picture of a low-flying A-10 attack plane warns Serbs: "Don't wait for me!''

Next to photos of a burning building in Belgrade and of Yugoslav leader Slobodan Milosevic, a different flyer asks, "Is it really his to gamble?''

And on another, NATO offers Serbs a blunt equation: ``No fuel, no power, no trade, no freedom, no future = Milosevic.''

Since April 3, officials said, allied planes have taken to the Balkan skies at least 14 times to unload one of NATO's nonexplosive weapons on Yugoslavia: propaganda. The alliance has dumped more than 36 million leaflets on at least 12 cities or areas throughout Serbia.

"The goal is to get the true story of what's happening to the Serbs,'' said Navy Captain Stephen Honda, a spokesman for US forces supporting the Yugoslav campaign, Operation Allied Force. "We are bypassing the government-controlled media to provide factual information to the Serbs. We want to tell the people what their government is doing.''

But leaflets with pictures of buildings in flames and streaking helicopters do little to inform or rally support for NATO, critics said; they do more to threaten and spread fear.

Furthermore, provocative leaflets make strong statements without citing evidence. Leaflets that say, "Heads of families have been pulled from the arms of their wives and children and shot,'' are probably viewed more as propaganda than credible information, says longtime observers of propaganda campaigns.

"The military doesn't have a particularly good track record when it comes to dropping leaflets,'' said Jarat Chopra, chairman of the international relations department at Brown University in Providence. "You have to consider who the target audience is.''

Chopra cited several examples of failed leafleting. In the 1992-1994 Somalia intervention, US forces ignored two important factors before dumping thousands of flyers in English: Few Somalis speak English and fewer can read the language.

In Namibia during the 1980s, Chopra said, leaflets were written in Afrikaans, then the official language of South Africa, which was offensive to many Namibians. And they were so poorly dispersed they drifted past population centers and ended up as fodder for goats.

"In Yugoslavia, the philosophy that the truth will prevail might very well work,'' said retired Army Colonel Douglas Lovelace, director of research at the Army War College's Strategic Studies Institute in Carlisle Barracks, Pa. "But it might have the reverse effect. Serbs are used their own administration, which operates by delivering propaganda. So the more you drop, the less they might believe.''

But even if the Western perspective pervades Serbia, it is unlikely to dent public opinion, Lovelace said. Months of continuous bombing have increased support for Milosevic, despite popular resentment of his rule.

NATO propaganda efforts have not been limited to scattering literature. Every day an Air Force EC-130 Hercules cargo plane flies along the perimeter of Serb airspace, beaming at least four hours worth of radio and TV programming into Yugoslavia.

The $70 million flying broadcast station began its mission in this conflict shortly after NATO's bombing campaign started on March 24, when Secretary of State Madeleine K. Albright, who spent part of her childhood in Belgrade, recorded a message in Serbo-Croatian that was aired in Yugoslavia.

Since then, the Hercules has beamed daily still images onto Serbia's Channel Two, showing pictures of Kosovar refugees and advertising the one AM and three FM radio stations that carry the US government-funded Voice of America and Radio Free Europe Serbo-Croatian services.

"The radio and TV campaign tries to address the atrocities in more detail than the leaflets,'' Honda said. ``But there's no guarantee the signals will always make it through. And it's pretty difficult to gauge the numbers of people actually listening.''

Yugoslav jamming of NATO's signal and the alliance's own bombing of electrical grids makes broadcast an unreliable source of propaganda. So NATO has resorted to dropping leaflets, a practice refined since at least World War I, when airplanes became a fixture of war.

Today, the US military psychological operations units have special equipment to design and drop leaflets. Years of experimenting, propaganda experts said, have found a leaflet will fall closest to its targets if it's 6 inches by 3 inches and weighs slightly more than normal paper.

"You can't put enough information on a leaflet,'' said retired Lieutenant Colonel Mike Furlong, who commanded the Army's 6th Psychological Operations Battalion in Bosnia until 1997. "But the goal is to plant a seed of doubt. If a soldier in the field has a second thought, if for a minute he thinks he might die if he stays and fights, then the goal of the leaflet has been accomplished.''

Copyright, The Boston Globe

By David Abel | Defense Week | 4/19/1999

SKOPJE, Macedonia -- The soldier who would lead ground troops or peacekeepers into Kosovo sat cross-legged in front of a wall of maps detailing the inhospitable terrain of the southern Balkans.

He had little time to mince words or speculate on hypothetical scenarios. He looked dour, spoke in crisp sentences, and brooked little tolerance for skepticism.

"Our mission is simple: It's to be prepared to implement a peace agreement in Kosovo," said British Lt. Gen. Sir Mike Jackson, who commands the 12,000 NATO soldiers assembled in Macedonia by the Allied Command Europe Rapid Reaction Corps. "We decided to put forces in early during the Rambouillet negotiations process so that they can move very quickly to implement any agreement."

They could be asked to move quite quickly indeed. Under a peace proposal by the European Union that was gaining diplomatic momentum late last week, if Belgrade agreed to begin withdrawing troops, then Western ground forces would immediately and simultaneously step in to take control of the province. Though it has requested membership in NATO, Macedonia has ruled out allowing the alliance to launch an invasion from its soil.

In an interview Thursday with Defense Week at his headquarters in an old shoe factory on the outskirts of Macedonia's capital, the 55-year-old Jackson explained how his role as commander of NATO forces in the region has required him to do everything from responding to the massive refugee crisis and ensuring troops are ready and well-protected to soothing diplomatic tensions with local authorities.

He would not talk about the possibility of invading Kosovo, Serbia's violence-wracked province whose border lies just 15 miles north of downtown Skopje. But he acknowledged NATO leaders could soon ask him to lead forces into Yugoslav territory. Jackson knows a land war could be long and grueling. He knows that Serb guerillas and Partisans plagued Nazi German occupiers during World War II, and he knows a small, motivated army operating on familiar territory can inflict pain on a larger, better-equipped invading force.

"It is mountainous, wooded terrain, and it lends itself to irregular warfare," he said. "I am a general student of military history. I'll leave it at that."

Jackson took over the Allied Rapid Reaction Corps in early 1997, soon after serving for nearly two years as the commander of the British army's 3rd Division, which acted as headquarters for the Multinational Division Southwest at the start of the NATO peacekeeping mission in Bosnia.

Now, the one-time paratrooper who served in Northern Ireland in the 1970s and helped plan Britain's invasion of the Falkland Islands in 1982 has partial command over nearly 500 U.S. soldiers in Macedonia. While American troops take orders from their own superiors, Jackson directs all forces in Macedonia in matters of how to work together and how to maintain a joint defense.

He also has to coordinate and keep the peace with the Macedonian government. As the weeks of the NATO bombing campaign piled up, and more bombs rained from allied planes over Serbia, soldiers under Jackson's command from Britain, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, the United States and Norway were digging in late last week. Every day their temporary forts appeared more permanent.

Ensuring the alliance retains its welcome has become an increasingly trying task. Soldiers patrolling the border and driving their military vehicles through local cities are frequently pelted by rocks and bricks. Jackson says he is in frequent contact with Macedonian police and government officials. He has directed the alliance's 35 helicopters in Macedonia to avoid flying through urban areas, especially in Skopje. He has also banned the driving of tanks and other earth-scarring vehicles unless absolutely necessary.

"[Macedonians] are obviously concerned about the number of NATO soldiers, the effect that has on the economy, the environment and all of that," he said. "It's my job to make sure that the Macedonian government does not have cause for complaint."

There were few protests, however, when Jackson helped implement the alliance's heroic response to the hundreds of thousands of refugees expelled from Kosovo since NATO began its bombing campaign March 24. He is proud of the way the soldiers have built tents, distributed food and brought calm to thousands in such quick fashion.

Still, he supports the transfer of the camps' authority from NATO to international relief agencies and the Macedonian government, even though many refugees say they fear the local police.

"As a point of principle, soldiers should not run refugee camps," he said. "That's not what soldiers are for. Refugees are better looked after by civilian organizations."

The military's primary role is to fight or to halt fighting, he said. Despite critics who question NATO's cumbersome balance of 19 nations with different cultures and militaries, Jackson argued that this multinational force is effective and represents the future in fighting wars.

The only gripe he admitted is that NATO is geared still for large-scale conflicts envisioned during the Cold War, not for small-scale, high-intensity conflicts such as pushing a guerilla army out of a small patch of mountainous territory. But the track record so far proves NATO can do the job, he added.

"Is this multinational thing actually a shambles?" he asked. "It's not. It works .... We're all in the same game. Here to do the same job. It's a unity of effort."

Civilian pilots risk fire in aid drops to refugees

By David Abel | The Boston Globe | 6/5/1999

WASHINGTON - An aging cargo plane chartered by a private relief group dropped 2,000 emergency meals intended for refugees trapped inside Kosovo yesterday, and it was set to fly again Monday on a mission that NATO said was too risky for its own pilots.

Yesterday's pre-dawn flight by the Soviet-built Antonov 26 followed an inaugural mission Thursday that was hampered by technical problems. The plane returned safely to Pescara, Italy. The crew reported no antiaircraft fire.

The plane, hired and manned by pilots from the former Soviet republic of Moldova, dropped the 2,200-calorie vegetarian meals in hopes the food would reach some of the 600,000 Kosovars going hungry after being driven from their homes. Many are said to be living off leaves and tree bark.

The project is backed by the US Agency for International Development, which is picking up a tab of about $1 million a month for 32,000 military-style meals per week. The bright-yellow packets contain peanut butter, lentil stew, jam, crackers, and rice pilaf.

Ed Bligh, a spokesman for the the New York-based International Rescue Committee, acknowledged the group is sending each crew of six into harm's way, lower and slower than any NATO aircraft has flown or is likely to fly.

Although a peace plan has been approved by Yugoslavia, hostilities have continued until NATO has strong signs of a Yugoslav withdrawal from Kosovo.

"I wouldn't call this a suicide mission, but it's definitely not safe," Bligh said. "We're trying to call as much attention to these planes as possible."

Though the Antonov plane - and another joining the effort next week - have been painted white with bright orange stripes, and Yugoslav and NATO officials have been informed about their mission, the planes are flying through dangerous airspace, where bombs frequently rain from above and antiaircraft fire bursts without warning from below.

Furthermore, the Yugoslav government told the International Rescue Committee it "will not give permission" for the flights, Bligh said. NATO said the relief group is coordinating its flight plans with allied commanders but the alliance could not guarantee its safety.

"I think they're brave to take the risk," Air Force Major General Chuck Wald told reporters at a Pentagon briefing Wednesday. "But if I were recommending it, I would not recommend they do it from an operational perspective."

In recent years, the US military rarely has been keen on airdrops. The work is dangerous because the large cargo planes must fly slowly and as low as possible to land the supplies on target. Moreover, military officials argue, the aid frequently does not reach the intended recipients, sometimes causes more harm than good, and the hefty military cargo planes are easy targets.

Shortly after the Gulf War, when humanitarian supplies were dropped to Kurds who had fled to northern Iraq, the heavy crates caused death and injuries.

During the civil wars in Somalia and Ethiopia, drops of food and medicine often ended up in the hands of warring soldiers instead of the starving victims.

In Bosnia, NATO planes flying humanitarian missions frequently became the targets, and sometimes casualties, of Bosnian Serbs firing antiaircraft weapons.

Scott Terry, a former Navy lieutenant who flew surveillance missions over Bosnia, outlined the principal means of delivering humanitarian aid by air.

The first is high-level parachute drops, which are inaccurate, although relatively safe for the aircraft and crew. A complicated low-level parachute system is designed for peacetime drops and not for a plane in firing range. The third, the method being used over Kosovo, is specially packaging the supplies to be dropped without parachutes, considered the quickest and most accurate.

But it is also one of the most dangerous. The airplane has to fly anywhere from 100 feet to 500 feet above ground and fly at one-third its normal speed.

Weapons replacement spells money for Raytheon

By David Abel | The Boston Globe | 6/10/1999

WASHINGTON - It was just after 7 in the Adriatic Sea on the first night of NATO's strikes on Yugoslavia when a British sub neared periscope depth, opened several of its torpedo doors, and let fly a volley of blast-belching Tomahawk cruise missiles.

The attack's significance went beyond the fact that it was the first time such weapons were fired by a nation other than the United States. The launching heralded a boon for the nation's third-largest military contractor and the maker of Tomahawk, Lexington-based Raytheon Co., which said last week that it expects to earn $1 billion to replenish spent stocks from the Yugoslav air campaign.

Since that night in late March, the British have fired nearly half of the 65 cruise missiles they bought earlier this year from Raytheon. And those sea-skimming precision munitions are only a fraction of what the US Navy launched against Yugoslavia and other foes in the past year.

Though the information remains classified, Navy sources say the United States has fired more than 600 of the $1.2 million sea-launched cruise missiles in the past nine months, including more than 220 in Yugoslavia, at least 330 during attacks on Iraq in December, and about 80 in strikes against targets last summer in Sudan and Afghanistan.

That spells a familiar word for Raytheon: M-O-N-E-Y.

Indeed, President Clinton signed an emergency-spending bill last month that earmarked $12 billion for the air war. Of that, $420 million will go to update 624 older Tomahawks to the newer, more effective versions. In addition, the Pentagon will divide $1.1 billion between the services to replace used bombs and missiles.

"We will be lobbying for this money to go to increasing our Tomahawk capability," a senior Navy official said. "It's our weapon of choice."

One area where some of the extra money from the emergency bill might go is to arming Britain. While London has requested an additional 30 cruise missiles, British military officials say they will need hundreds to supply 12 Tomahawk-capable attack submarines by 2003.

Those extra Tomahawks will not come off Raytheon's production line, which closed in January, but from the Navy's remaining supply of 2,200 such cruise missiles. Still, the $20 billion company would profit in at least two ways.

Raytheon would benefit from the millions of dollars it would cost to upgrade to the "Block III" Tomahawk, which flies farther, requires less fuel, and packs a stiffer punch than the older "Block IIs." Currently, more than half of the US Navy's arsenal consists of the less-advanced cruise missiles.

The other benefit to Raytheon is the Navy's decision to accelerate production of the next-generation Tomahawk. The cruise missiles launched in Yugoslavia and increased British demand pushed the Navy to request Raytheon to produce six times the number of planned "Tactical Tomahawks" in its first year of production in 2003, a Navy official said.

"This is certainly good news for Raytheon," said Paul Nisbet, a military analyst at JSA Research in Newport, R.I. "The sooner they deliver, the better."

The overall number of Tactical Tomahawks, which are supposed to cost 40 percent less than current versions and fly 30 percent farther than Block IIIs, that the Navy plans to purchase from Raytheon will remain 1,353.

The next-generation Tomahawks are just one of many defense contracts fueling a resurgence at Raytheon, which had sales of $4.9 billion for the quarter ending in April. The defense giant's portfolio includes the Army's Patriot missile defense system, expensive new missiles such as the Joint Standoff Weapon, and most recently a multimillion-dollar contract to develop a new radar system for future aircraft carriers and destroyers.

Still, replenishing Tomahawks by upgrading the older ones and accelerating the production of newer ones promises to account for a large chunk of Raytheon's future revenue.

By David Abel | The Boston Globe | 6/10/1999

WASHINGTON - If it isn't their slow glide over enemy positions, or their inability to evade ground fire, it's probably the drone's buzzing that made it such an easy target.

While only two NATO aircraft went down in more than 33,000 missions since the strikes against Yugoslavia began March 24, at least 22 allied unmanned aerial vehicles crisscrossing the skies over Kosovo in a fraction of the missions fell victim to either enemy fire or mechanical failure. That includes a dozen US drones.

The small, remote-controlled aircraft have been where no pilot has dared to go - sometimes only a few thousand feet above entrenched Serbian forces. And while sometimes the 17- to 27-foot-long planes did not make it back to their bases, they often relayed enough information to have piloted aircraft return and avenge their sacrifice.

"Actually, I'm surprised they held together as well as they did," said John Sundberg, the deputy manager of the Army's unmanned aerial vehicle program in Redstone, Ala. "They're designed to be used and abused."

The drones, which range in cost from nearly $1 million for the Navy's low-flying Pioneer to as much as $3.5 million for the Air Force's high-altitude Predator, have been used over Kosovo for a variety of missions, including aiding pilots in other aircraft to aim precision-guided bombs, photographing troop movements and assessing battle damage.

But the current lot of drones are relatively primitive devices, sent off by crews with little experience using them in combat.

The significantly increased use of the drones, which are essentially flying cameras and radio relays, probably contributed to their rate of malfunction, said Daryl Davidson, the executive director for the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International in Washington. In addition to downed French and German drones, the Navy has lost two Pioneers and the Air Force has lost three Predators.

"They are being used in situations that are new, and that adds a lot of stress," Davidson said. "There are going to be problems, and we are learning valuable lessons. But it's not much news when they're shot down, unlike when a pilot is captured or three soldiers are taken prisoner."

Unmanned aircraft were designed for missions too risky for pilots. Although they have been around in various forms since World War I, drones did not play a serious role in the US military until the Vietnam War.

By the mid-1970s, unmanned Air Force planes flew more than 3,000 reconnaissance missions over North Vietnam and China. With that experience and after the Israelis' noted use of drones to destroy Syrian air defenses in Lebanon, the Pentagon launched its first modern unmanned aircraft, the Pioneer.

The new drone, which has been used in the Gulf War, over Bosnia, and in NATO's conflict with Serbia, now plays third fiddle to the more advanced Hunter and Predator.

While each carries a set of video cameras and infrared equipment, the Predator doubles what the Hunter can carry and multiplies by four times the Pioneer's lift capacity. Moreover, the Predator can stay aloft for more than 20 hours, whereas, the Pioneer must return to base within five hours and the Hunter within 11 hours.

Still, the more advanced drones do not compare to the sophisticated unmanned aircraft the Pentagon is now designing. Future drones, which will range in expense from $300,000 for an Army field scout to $10 million for an Air Force plane that provides a "god's view" of the battlefield, are likely to employ the lessons learned from Kosovo.

By David Abel | The Boston Globe | 6/20/1999

WASHINGTON -- Three days after NATO began raining bombs on Yugoslavia in late March, hackers in Belgrade began flooding the alliance's headquarters in Brussels with thousands of e-mails and potent computer viruses, eventually forcing NATO to temporarily take its system off line.

Later, officials briefly shut down the White House's official Web site after someone with a computer and a gripe against the war breached its well-protected system.

And not long after that, a group of Chinese hackers unleashed their anger over the United States' accidental bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade, scrawling graffiti and denouncing NATO's "Nazi action" on the home pages of the departments of energy and interior.

These were a few of the thousands of attacks on allied computer systems in what Pentagon officials call the first cyber-war.

"We experienced at least 80 to 100 of these intrusions a day during the war," said Susan Hansen, a Pentagon spokeswoman, who said the Defense Department has launched a review to study the attacks and responses. "As with all computer systems, there are vulnerabilities. But we are increasing our defenses."

The Pentagon would not say how it determined that the attackers came from Belgrade and Beijing, nor would it discuss specific countermeasures.

The flurry of cyberspace attacks did not surprise the Pentagon, which for years has been the target of scores of daily Internet-based assaults.

Just a month before the bombing campaign began, Deputy Secretary of Defense John Hamre detailed to Congress the havoc cyber-warfare could wreak.

With about 95 percent of the Pentagon's communications over open lines such as the Internet and commercial phone lines, the Defense Department's activities could be severely hampered if either were disabled, he said.

Furthermore, the Pentagon is trying not only to protect major systems from sabotage by hackers and spies, he added, but from disaffected employees.

"In the past, much of our defensive efforts were to protect our offensive capabilities," Hamre told the House Armed Service Committee in February. "Now we have to protect an extensive Pentagon information infrastructure - virtually all of which depends upon the commercial communications networks - because we simply cannot conduct and sustain offensive operations without these critical infrastructures."

While the cyber-attackers were more of a nuisance than a nemesis, officials say the campaign underscores the growing threat.

What if hackers breached the computer systems of the National Imagery and Mapping Agency and altered maps? Or found a way to filch targeting plans from NATO computers? Or lodged a virus in software used by bombers to aim their weapons?

These are the hypothetical scenarios that trouble Dan Kuehl, a professor of information warfare at the National Defense University in Washington.

"What worries me is not the graffiti, but people subtly changing content," Kuehl said. "Let's say a few words are changed on a corporate Web site, that could have a significant effect on the price of that company's stock. And then imagine the same thing on the State Department's Web site. That could be very serious."

Since the war began, the Pentagon has moved to shore up its computer defenses, officials said. Using some of the $3.6 billion budgeted between this year and 2002, the Pentagon this month began moving the majority of Internet traffic from a commercial service provider to a protected in-house server.

In December, the Pentagon established the Joint Task Force for Computer Network Defense, a 24-hour information protection nerve center that continuously monitors the military's computer systems and stands ready to respond to attacks.

The joint task force recently set up an information operations system similar to what the Pentagon uses to assess the threat of nuclear war. On a scale that ranges from Normal to Delta, the task force during the war set the country one notch above the lowest threat level.

"This reflected our level of concern for the attacks," said Melissa Bower, a task force spokeswoman. "It wasn't great."

But what Bower and others read from the computer attacks is a warning for the future. Anything from the nation's banking system to the air traffic control system potentially could be held hostage during a cyber-war, they fear.

Dorothy Denning, a computer scientist and information warfare expert at Georgetown University, said she could imagine all kinds of devastation a savvy hacker with a vengeance could inflict. The nation's vulnerability is increasing, she said, as people rely more on computers.

"The consequences could be tragic," Denning said. "Our systems will never be absolutely secure. But we can't live in a totally walled-off community. This is the future."

Pieces fall into place for assault by land

By David Abel | The Boston Globe | 5/27/1999

WASHINGTON - With the pounding being taken by Yugoslav soldiers in Kosovo, NATO may need little more than the extra troops and arms the alliance approved this week to launch a ground war, military analysts say.

Allied forces have agreed to increase the number of peacekeeping troops from 27,000 to about 50,000. Meanwhile, military planners have urged NATO to prepare for a ground invasion before the allies are forced to fight through the winter.

The troops and armament, which would be added to a force of about 25,000 NATO soldiers in Macedonia, Albania, and aboard amphibious ships in the Adriatic Sea, might itself constitute a viable invasion force, rounding out a formidable core of heavy tanks and attack helicopters in the region.

"This isn't just the first step or the camel's nose, it's the front half of the beast," said Dan Goure, a former Pentagon strategist and now a military analyst at Washington's Center for Strategic and International Studies. If Yugoslav leader Slobodan "Milosevic doesn't cave in by early June, NATO will have to prepare to force him out."

Although alliance officials emphasize that the buildup is meant to strengthen NATO's ultimate peacekeeping mission, Goure said the alliance's decision to bolster its forces was the beginning of an "immaculate deployment," which would bypass debate over a ground buildup among NATO's 19 members and keep the pressure on Milosevic.

He and other military analysts said such a strong base of troops could be easily enhanced shortly before the alliance made a decision to invade.

In an April study on NATO's ground war options, James Anderson, a defense policy analyst at The Heritage Foundation in Washington, estimated that the allies would need only 50,000 to 70,000 troops to drive Yugoslav forces from Kosovo.

"I think these numbers depend on how well the air war goes," Anderson said. "After two months more of air war, we may need even less troops."

In his study, Anderson analyzed land war scenarios ranging from merely arming the Kosovo Liberation Army to launching a massive ground assault to occupy all of Yugoslavia, including Serbia's democratic sister republic, Montenegro. The former option would require about 10,000 troops for training and would cost the United States about $1 billion, he said; the latter could require up to 500,000 troops and leave US taxpayers with a bill of more than $50 billion.

Pushing the Yugoslav forces from Kosovo, he said, would take about a month, cost between $5 billion and $10 billion, and allied casualties could surpass 2,000.

In another study on ground war options, Anthony Cordesman, a senior fellow for strategic assessment at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said NATO has many options for building a heavily armored ground force in less than two months. In addition to the 25,000 already there, NATO could draw upon the 8,200 US Army forces from the First Cavalry Division it has stationed in Bosnia, 41,500 soldiers from France's Rapid Reaction Force, and a force of 165,000 troops from the Italian Army.

More likely, however, the force would be contain at least two main US divisions, probably the Army's 101st Airborne Division based at Fort Campbell, Ky., and the 10th Mountain Division based at Fort Drum, N.Y., Cordesman said.

Assuming the additional forces arrive in the region, the allies would have to reach a consensus to invade. Given recent statements against such action in Germany, Italy, and Greece, among other member nations, such a consensus could be difficult.

NATO officials said military planners will present a "force generation" plan to the North Atlantic Council, the alliance's top policy-making body, before the end of the month.

A newspaper report indicated today that a much larger allied force may be in the offing.

The Times of London reported today that President Clinton is ready to consider sending up to 90,000 US combat troops if no peace deal emerges within three weeks.

The newspaper quoted unidentified NATO sources for its information, Reuters reported.

There was a growing feeling in Washington and London that NATO must prepare for an operation involving 150,000-160,000 troops, the Times said.

By David Abel | The Boston Globe | 5/26/1999

WASHINGTON - NATO warplanes strafe a Kosovo Liberation Army base. A laser-guided missile slams into a hospital in downtown Belgrade. Western reporters at a bombed-out prison run for cover when NATO planes zoom in for another run.

These cases of so-called collateral damage were reported in the past week, all after the bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade, which jeopardized relations with Beijing and prompted worldwide condemnation.

Despite pledges by top military leaders to review the causes of such incidents as they mount in the 63-day air campaign, NATO has not altered its targeting or attacking procedures, alliance and Pentagon officials said.

"No, nothing has changed," said Canadian Major Ric Jones, a NATO spokesman in Brussels. "I am not aware of any new guidelines."

He said the alliance says its record has been very good and errors such as the Chinese Embassy bombing rare. Jones noted the distinction between a bomb that hits the wrong target because the targeting information is wrong and one that malfunctions.

NATO can do little to prevent a missile from missing its target or damaging surrounding buildings when it hits the target. However, the onus falls on the alliance when its mission planners give pilots faulty information, as with the attack on the Chinese Embassy and the rebel base, Jones said.

In both cases, NATO said its failure was in giving pilots out-of-date information. Databases did not register the Chinese Embassy's new address, and news that the rebels had seized a Yugoslav Army garrison six weeks before NATO's attack never reached Brussels.

"The problem is poor intelligence, planes are not flying low enough, and we're waging a war by committee," said retired US Army Colonel William Taylor, director of political-military studies at Washington's Center for Strategic and International Studies. "This is a really dumb way to fight. . . . No one is accountable without a single chain of command. And you can't expect not to lose planes. It doesn't work."

Taylor and other analysts doubted the alliance would change the way it chooses or attacks targets. A senior congressional military analyst fumed when commenting on an internal e-mail that asked State Department employees to alert the Pentagon, after the Chinese Embassy bombing, to any other foreign missions that had recently moved their quarters. "You mean the intelligence community has to ask?" he said. "They don't already have this information?"

NATO bases its targeting decisions on sources ranging from agents on the ground to satellites keeping a watch from orbit.

Many fixed targets such as fuel refineries, arms depots, and army barracks are well known, and their locations are stored in classified databases. Fresh targets, such as arise when a military convoy moves on an open road or an enemy unit establishes new headquarters, often require nearly instantaneous information, and rely on a pilot's ability to identify the target.

"Our information is usually very accurate," said a Pentagon official who is reviewing US military strategy. "The problem is not identifying a truck moving on a road, but what's inside the truck."

The Pentagon's chief agency coordinating satellite intelligence over Kosovo is the National Imagery and Mapping Agency. It's the agency blamed for drawing up the outdated map that resulted in the Chinese Embassy bombing and for errors predating the Kosovo conflict, including questionable maps used by the crew of a Marine Corps jet that struck a ski-lift cable in February 1998 near Aviano, Italy, killing 20 people.

The three-year-old agency, which combined departments of the Pentagon and the CIA, was created after the Gulf War to speed battlefield intelligence to commanders in the field. Since then, it has been responsible for pinpointing potential military targets throughout the world. And, despite its much-publicized failures, the agency is fulfilling its mission in Yugoslavia, officials say.

Colonel Richard Bridges, a senior Pentagon spokesman, said errant bombs and faulty targeting account for less than 1 percent of the more than 15,000 strikes launched since NATO started its air war against Yugoslavia March 24. He said the alliance had no reason to change the way it identifies and attacks targets.

"There has never been a war fought with this level of exactitude," Bridges said. "But we can't guarantee a risk-free war. The bombs we drop are designed to kill people."

Copyright, The Boston Globe