By David Abel | Houston Chronicle | 4/10/1999

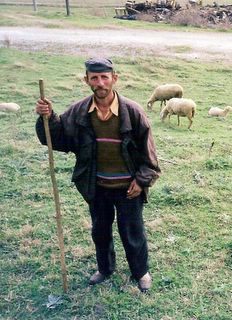

BRAZDA, Macedonia - To the sheep farmer, the scores of red government buses rounding the narrow road seemed like part of the normal flow of traffic between Yugoslavia and Macedonia.

Little did Fahdil Seruhe know that the buses rumbling through his valley were packed with thousands of weary ethnic Albanian refugees from Kosovo.

And little did Seruhe, an ethnic Albanian himself, realize that the land where his sheep have grazed for the past 20 years was surrounded by Europe's most chaotic refugee crisis since World War II.

"What crisis? I haven't heard about a refugee crisis,"

said Seruhe after he chased a stray sheep from the busy road. "I don't like politics. I try not to get involved."

said Seruhe after he chased a stray sheep from the busy road. "I don't like politics. I try not to get involved."The refugee crisis took some local villagers by surprise. Yet in the 17 days since NATO began raining bombs on Yugoslavia, two massive camps have sprung up near this illiterate 42-year-old farmer's grazing grounds.

NATO officials say that what had been a chaotic response to the refugee influx in the war's first two weeks now is being shaped into a coordinated effort.

"The humanitarian effort continues to gain momentum, and I think it will be a matter of days before we have the situation quite under control," Sadako Ogata, the head of the U.N. refugee agency, told an Associated Press reporter.

South of Seruhe's land, where the buses were headed, stands a new tent city that was built to accommodate up to 100,000 refugees. In less than two days, NATO troops mainly from Britain, France and Italy erected the sprawling camp with the help of at least 50 U.S. Marines.

The NATO camp sports rows of sturdy new tents rushed from the United States, Italy and Britain. Multiple food stations are supplying about 30,000 refugees with bread, chicken, military rations and potable water. There are medical facilities. More importantly, refugees say, there is a sense of security.

"When the Serbs forced us to leave Pristina and said they would kill us if we didn't, it was bad," said Lindita Latife, 21, who studied math at a university in Kosovo's provincial capital.

"Then we got to the border, and the Macedonians treated us like animals," Latife said. "First, they wouldn't let us enter. Then they made us sleep on the open, wet ground. And then they beat us when we complained. It's only now that we have some peace. This is a great place - even if I still can't take a shower."

To the north of Seruhe's fields - in a border settlement called Blace - stand the remnants of a ramshackle camp where Latife and thousands of other ethnic Albanians stayed until they were removed by Macedonian police earlier this week.

The empty area is a portrait of squalor. Human waste, bottles and hastily discarded possessions and clothing litter the muddy paths.

The makeshift tents in the camp had offered little protection from the cold rain. Food had become scarce, and diseases such as respiratory viruses and skin rashes had flared.

At least 40 people are reported to have died at Blace, according to the U.N. refugee agency.

The Macedonian government, which has been overwhelmed by the flood of refugees, controlled the Blace border camp. Troops surrounded the cramped grounds brandishing AK-47s. Human rights workers and other monitors were barred from entering the fields. And customs officials were responsible for the slow admission and release of the exiled Kosovar Albanians.

Many frustrated ethnic Albanians - who had been forced to wait up to four days in the open and in the range of Serbian guns in hopes of crossing the Macedonian border - have now returned to the interior of Kosovo, their fates unknown.

Some refugees are being settled in camps in Macedonia such as the NATO tent city at Brazda, which Ogata toured Friday. Others are being sent to facilities in NATO member countries or in Albania.

The United States and other countries have pledged to take thousands of refugees, but U.N. refugee officials indicated Friday that any plans to send the Kosovars to North America are on hold for now because of desires to keep them closer to their homes.

Critics have charged that the dispersal of refugees would only help Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic complete his apparent goal of ridding Kosovo of ethnic Albanians.

The residents at Brazda seem grateful. "The NATO troops have been wonderful," said Ramadan Ibrahimi, a 27-year-old taxi driver. "I saw them playing ball with children."

Despite the gravity of the refugee crisis, some Macedonian villagers such as Seruhe live as though nothing has changed.

The sheep farmer, who says he rarely ventures more than a few miles from his home, had no idea that bombs were falling on neighboring Yugoslavia or that thousands of his fellow ethnic Albanians had been driven from their homes.

He said he was merely enjoying the arrival of spring.

"I have a job to do," he said, "and that's what I do. I don't pay attention to conflicts.

"They don't make sense to me."