As exiles seek a life, Macedonia sees its delicate balance shift

As exiles seek a life, Macedonia sees its delicate balance shiftBy David Abel | The Star-Ledger | 4/14/1999

SKOPJE, Macedonia - Pushing his way through the frenzied crowd, Servej Bela scuffled to secure a place in front of a small window at the local Red Cross last week.

Unlike thousands of ethnic Albanians fenced in in camps, this 19-year-old was not seeking bread, shelter or medicine.

He, like hundreds of others, was pleading for Macedonian identity cards.

Thirty-three cousins from Kosovo, who have taken refuge with Bela's family in a cramped two-room house, need the cards so they can resume their lives. They want to go to school, get medical aid and qualify for food supplements from international relief agencies.

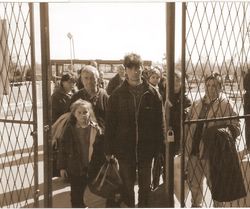

The university student, who found his Kosovar cousins less than two weeks ago in a squalid refugee camp on the Macedonia-Serbian border, left empty handed. Authorities in this small, bucolic country of 2 million people, one of Europe's poorest, are concerned that the influx of ethnic Albanians will severely upset their nation's delicate ethnic and political balance.

Local Red Cross officials would not say how many identity cards will be issued. However, government officials have clearly encouraged refugees to stay in camps and have resisted settling the exiled in Macedonia.

More than half of the estimated 125,000 Kosovars sent here since NATO began its bombing campaign on March 24 have been taken in by friends, family or other ethnic Albanian host families, according to the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees.

Before the war, ethnic Albanians accounted for at least 23 percent of Macedonia's population. That doesn't include an estimated 50,000 to 100,000 Kosovars who took refuge here last March as tensions mounted in their home province inside Serbia. And many fear, as the war continues, more will flood across the border.

Life for ethnic Albanians in this recently established country has improved since Macedonia gained independence from Yugoslavia in 1992. While as Muslims they have long been second-class citizens - the country is 70 percent Orthodox Christian - they find less isolation and more opportunities.

The nascent democracy,

the only Yugoslav republic to peacefully separate from the former Communist country, has increasingly incorporated ethnic Albanians into influential positions throughout the country. They hold several powerful ministerial positions, including the job of vice premier. In the most recent national election in October, for example, the winning party, which had more than 60 percent of the vote, welcomed an ethnic Albanian party into its coalition.

the only Yugoslav republic to peacefully separate from the former Communist country, has increasingly incorporated ethnic Albanians into influential positions throughout the country. They hold several powerful ministerial positions, including the job of vice premier. In the most recent national election in October, for example, the winning party, which had more than 60 percent of the vote, welcomed an ethnic Albanian party into its coalition.Still, discrimination continues. "The bottom line is there are long-standing tensions between the ethnic Albanians and Macedonians," said a U.S. diplomat at the embassy in Skopje. "The situation has gotten much better in recent years. But they aren't out of the woods by any means."

Macedonians worry that their country might turn into another Kosovo, Serbia's embattled southern province, with ethnic Albanians demanding independence or a "Greater Albania."

''That's what they want," says Vancho Petrov, 33, a Macedonian taxi driver, echoing comments heard from many locals. "I know these people. They will want to take a piece of our country for themselves."

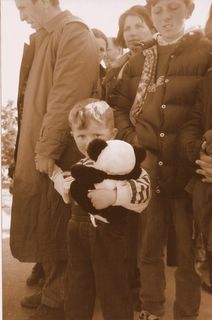

But inside Bela's dilapidated two-room home, his Kosovar cousins laugh at the idea of a greater Albania. They say they just hope to live in their country again. Thirteen of them are younger than 16 years old and have none of the exuberance of a gaggle of kids in such close quarters.

Bela says his cousins are in good hands at his home. But he isn't sure how long his family can bear the burden. For the last two weeks, all they have eaten is tea and bread.

''We need help," Bela says. "Who knows if they will ever be able to return to Kosovo. They need to have lives to live of their own."

The voice of Bela's 12-year-old cousin, Gadaf Shiti, is high pitched as he speaks of revenge and promises to join the Kosovo Liberation Army. His mother, who walked three days without food or water to reach the Macedonian border, says she approves of her son's desire to fight. Gadaf's aunt can't get up from a small bed. Her legs won't hold her weight. Too much walking, she says.

They don't know what they'll do if the war doesn't end soon. For now, they'll stay with Bela's family and try to live as best they can as ethnic Albanians in Macedonia, they say.

''Someday I will go back," vows Sheride Shiti, 30, Gadaf's mother. "But it will never be the same. There are too many tears."